– this was the title of a boundary-pushing exhibition held in the grounds of a military airbase in 1999.

The base, adjacent to the Norwegian Aviation Museum in Bodø, gave curators Karl Kleve and Bodil Nyaas an apt location in which to consider how the Cold War framed contemporary society. They had been keen, both told me during a fieldtrip to Bodø in June 2022, to look further than a traditional focus on the military ‘face’ of Cold War history. The callous, calcified interior of a nuclear-proof aircraft hangar provided an evocative contrast to panels about soft power, society, culture and emotions.

My visit to Bodø reminded me how difficult it is to interpret the many ‘faces’ of the Cold War in gallery spaces that often necessitate simplification and reduction. The premise of this research project is that collecting, displaying and communicating the Cold War in museums often falls short of being representative.

Cold War museology is challenging because it encompasses variety thematically, geographically, intellectually and socially. From regional contexts to hot wars, highly-specialised innovation to classified government files, cultural ephemera to intangible emotion, memory and myth, there is much museum professionals must consider when debating whether objects ‘fit’ a Cold War exhibition. As Bodil stated, the Cold War is ‘slippery’ – collections are easily categorised as ‘Cold War’ and equally, not at all ‘Cold War’.

… the Cold War is ‘slippery’ – collections are easily categorised as ‘Cold War’ and equally, not at all ‘Cold War’.

This is a definitional slipperiness that has concerned Holger Nehring too, who writes that a scholarly ‘‘decentring’ of the field away from its military and diplomatic core, has come at a substantial cost. The meaning of ‘Cold War’ as a concept has been diluted significantly so that ‘Cold War’ lurks everywhere and can be applied to everything, from high politics to the history of everyday life, from actions of statemen to the mundane’.[1]

What do museums do then, when museological approaches to this period are lacking, yet the concept and theory of what it was are disputed, sprawling and almost impossible to contain?

For many years the tangible, visible landscape of Bodø’s military Cold War has been over-privileged in the museum because it lends itself to interpretation and of course, because planes are popular. However, this abundance of military material obscures the pursuit of deciding what the Cold War was beyond aircraft and missiles.

In an effort to begin the process of integrating social interpretation (and research) with military galleries, National Aviation Museum colleagues are connecting tangible militarisation with the slipperiness of the Cold War in Norwegian history.

The town of Bodø was utterly transformed by the infrastructural transformation it underwent as a result of its strategic location on the northern Norwegian coast. Norway, recipient of Marshall Aid and subsequently Arms Aid, drew closer to the United States in the post-war years, and became a founding member of NATO in 1949. Bearing the only land border of any NATO country with the Soviet Union and a sea border extending to the increasingly militarised Soviet Kola peninsula, Norway was a vital defensive and offensive Cold War location.

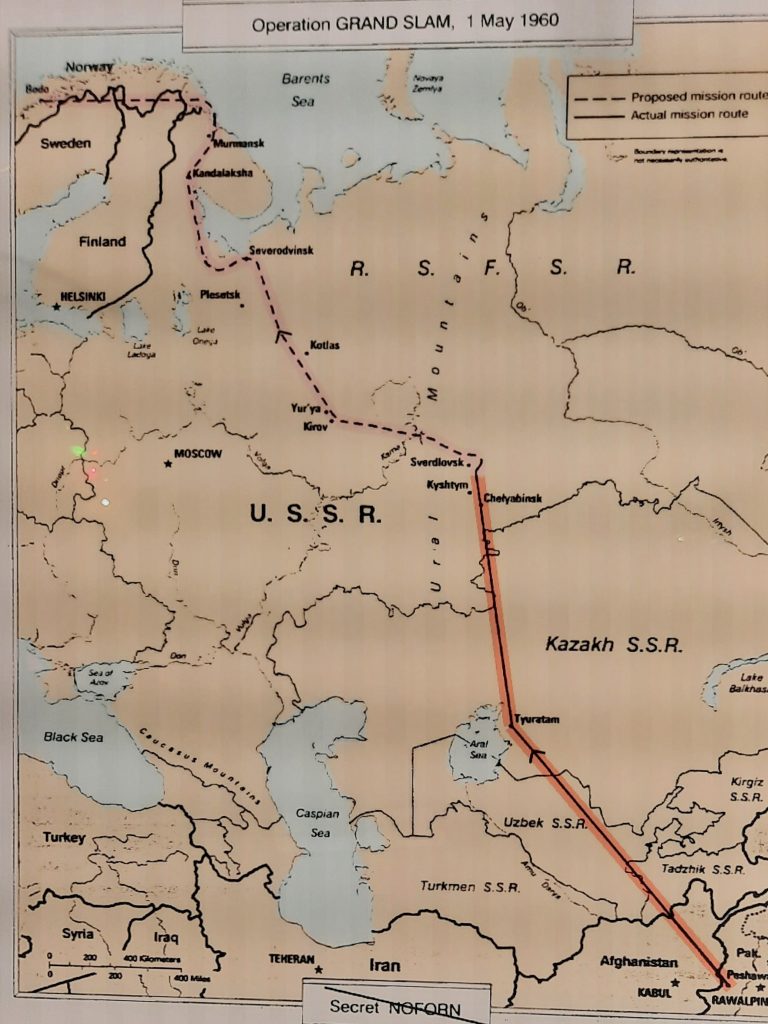

The air base at Bodø hosted two fighter squadrons at any one time and held regular training operations. It became the potential location for deployment of nuclear missiles in the event of war (this never transpired, of course), and it was equipped with an underground nuclear-safe hangar optimised to withstand a nuclear attack. Intelligence and reconnaissance operations were an established part of military life. Indeed, Gary Powers was flying from Pakistan to Bodø on the surveillance flight that was infamously shot down south of Sverdlovsk in the Soviet Union.

Museum staff repeatedly suggest that the people of Bodø, though largely ignoring the air base, or implicitly accepting its presence, had a paradoxical understanding of the inherent Cold War secrecy that governed it. One interviewee described her childhood habituation to the deafening roar of starfighters taking off and landing, at first horrifying, years later hardly noticeable. The presence of war simulation exercises sensitised civilian inhabitants to global issues and energised civil defence preparation. Bodø’s civil aviation boom paralleled developments in military infrastructure and concurrently made significant cultural and economic impacts on the region.[2]

The uniqueness of Bodø’s Cold War landscape reminds us not to be hoodwinked by jets and engines and keep critiquing the slipperiness of the Cold War.

The uniqueness of Bodø’s Cold War landscape reminds us not to be hoodwinked by jets and engines and keep critiquing the slipperiness of the Cold War. Can we decide instead that something is or is not Cold War in relation to its environmental and regional context? Can we keep grappling with the local conditions in which material becomes a ‘face’ of the Cold War past?

[1] Holger Nehring, “What Was the Cold War?” The English Historical Review 127, no. 527 (2012), 920–949, quote 923.

[2] Karl Kleve has written on the wider Cold War context of Norway’s civil aviation development: “Fearing the Eye in the Sky: How the Fear of Espionage Affected the Development of Civil Aviation During the Cold War”, The international journal of intelligence, security, and public affairs 22, no. 3 (2020): 307–327; ‘Making Iron Curtain overflights legal: Soviet – Scandinavian aviation negotiations in the early Cold War’ in Sune Bechmann Pedersen and Christian Noack (eds.), Tourism and Travel during the Cold War Negotiating Tourist Experiences across the Iron Curtain, (Routledge, 2019).