The Materialising the Cold War project will soon end. It has been a busy, productive three years, during which our research raised as many questions as it answered – not least because the developing global context altered the definitional lens on ‘Cold War’ topics. Reflecting on the ambitions and outcomes of our project, the team took one last fieldtrip to two Cold War heritage sites in York: the Yorkshire Air Museum and the York Cold War Bunker. Here, inspired by the day, Jessica Douthwaite records a few final thoughts on Cold War museology.

As we gingerly walk the frozen paths between airfields on one of the coldest days in the UK this year, our tour guide – a volunteer at Yorkshire Air Museum – describes his surprise when he realised that a newly accessioned Sepecat Jaguar XZ383 was one he had flown twice on duty as an RAF pilot in the 1980s. He wonders whether he’s become a museum piece himself. It is a joke that you have heard before from project participants with material relationships to Cold War objects housed in museum collections and one that remains pertinent. How do we account, as heritage professionals, for the rapid movement of things from living, breathing objects to historical artefacts, and how do we acknowledge their relationships with people and communities in the past?

In one sense, by involving those people, like this tour guide, in the heritage practices of the sites and collections themselves, you honour the living histories embodied by the people closest to those objects in their operational heydays. We touched on this too at York Cold War Bunker, discussing the power of large-scale oral history projects to add depth, granularity and humanity to existing collections and displays, particularly where topics like the Royal Observers Corps and civil defence revolve around interior worlds and emotionality.

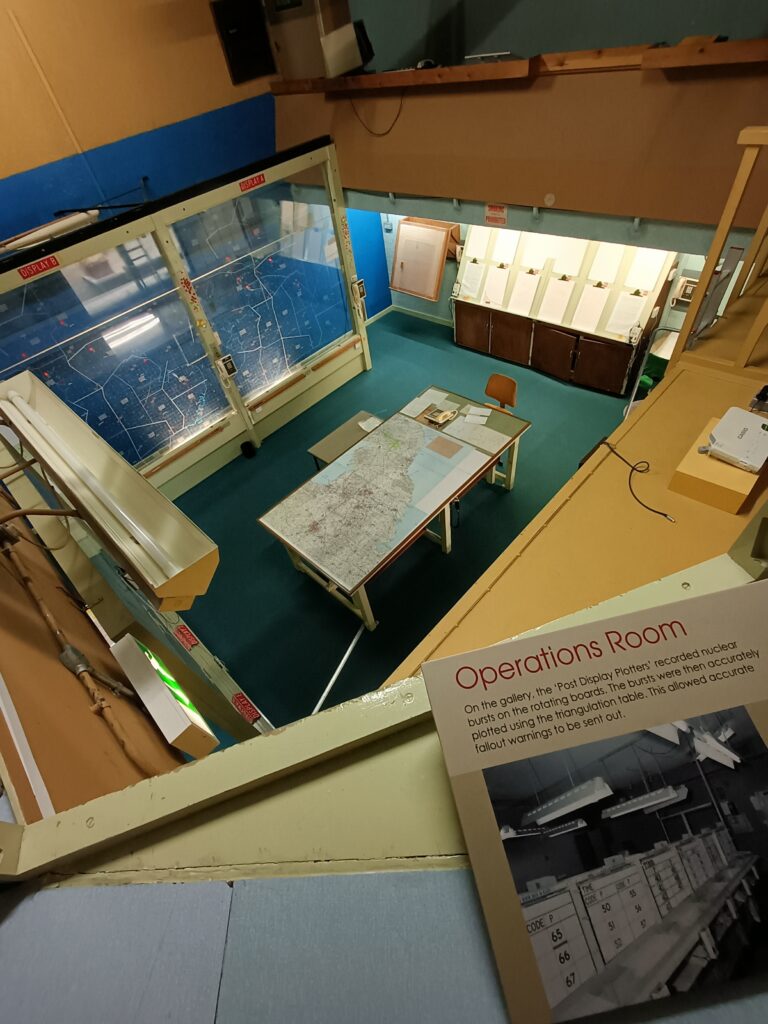

Inside the bunker, with English Heritage Senior Collections Curator, Kevin Booth, we noted the importance to tour groups of the ‘feel’ of the place. He reflected that as audiences gradually realise how this fairly mundane setting would be occupied in a real war situation their attention to the surroundings heightens: the buy-in of your visitors can change the whole atmosphere of a heritage site. Indeed, as the preservation of the bunker’s contents becomes an increasing concern to Booth, the authenticity of this ‘feeling’ and atmosphere is at stake. What happens when the Perspex, the mid-century wood and the paper ephemera of Cold War-era nuclear attack planning must be removed for conservation and replaced with replicas? Will visitors have the same experiences?

The airfield on which Yorkshire Air Museum sits – once RAF Elvington – was itself a strategic location for Cold War activities by the United States Air Force and the Blackburn Aircraft Company, though its name as a heritage attraction is predicated on the role it played in Second World War battles. The museum has a collection of offensive and defensive Cold War aircraft that have been united through a comprehensive Cold War interpretation design and narrative display. Panels and labels are visually different and highlight how, with simple interpretation strategies, a coherent history can be created in a setting where large, cumbersome objects are hard to explain.

Conversely, there are few interpretation panels at York Cold War Bunker, where an introductory film and a guide provide context to visitors. The differences in representation at the two sites is a reminder of the varying ways in which the Cold War has been, can be and will be displayed – depending on collections, audiences and expectations. What these places have in common is the variability of Cold War understandings amongst visitors: the fact that as we move away in time from the end of the Cold War a large proportion of the public have no personal memories of the period and might glean impressions of its history (if any) as much through popular culture as through research-based outlets.

Our project has shown that while Cold War heritage-making sites and institutions differ across the sector they are united by their role in bridging gaps in understandings of the Cold War through research, and creating spaces for thought and conversation about its broad and far-reaching impact.

———————————————————————————–

Our National Museums Scotland outputs can be found here. The Cold War Scotland exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland runs until January 2026. Our Cold War Scotland book is available from the NMS shop here and Cold War Museology is published open access by Routledge here.